About two years ago, SophosLabs published a paper entitled Vawtrak – International Crimeware-as-a-Service. The paper explained how hackers have adopted the “Pay As You Go” model which has become very popular in the mainstream technology industry.

Hackers have provided services to one another for years by trading spamming lists, writing malware programs to order, and finding and selling vulnerabilities. However, after you’ve provided another bunch of cyber criminals with your malware source code files, or with access to your mailing lists, you can’t control what they do with them. In fact, what is usually referred to as Crimeware-as-a-Service, or simply CaaS, has changed all that.

CaaS crooks keep their malware to themselves, alongside automated tools for generating new variants, techniques for rapidly customising the malware payloads, as well as the network which they use to push out infected files to potential victims.

Hackers don’t sell the malware itself, but a malware delivery service on agreed terms. For instance: N passwords stolen from X users of bank Y in country Z. In other words, CaaS “customers” in the cybercriminal underworld pay for results, without having to worry about, or even to understand, the technological tricks needed to mount a successful malware attack.

In 2014, SophosLabs concluded: “This model allows specialisation. Aspects of the operation can be divided into distinct areas that expert members of the team can work on independently. For example, German language web injects can be handled by German speaking team members; code that is designed to bypass two-factor authentication can be written by a different team than more simple code that asks for extra information not normally required, and the stolen data can be similarly divided.”

A sneaky trick used in banking-related malware is called web injects. It acts like Vawtrak which steals sensitive user data. The purpose of the phishing attacks is to trick you to fake banking websites, hoping that you’ll enter confidential data where it will be stolen.

While Web injects wait for you to visit a genuine banking website, so that all the security indicators in your browser are correct.

Finally, the malware modifies the web pages from the genuine website, altering them in memory after they’ve been decrypted and authenticated, but just before your browser displays them.

In other words, the malware can grab secrets such as passwords by presenting you with fake fields on otherwise legitimate pages on legitimate websites – an altogether harder trick to spot than traditional phishing.

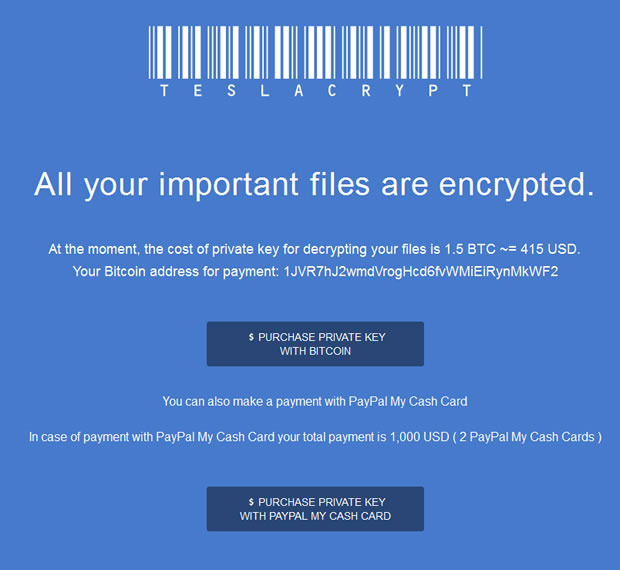

Nevertheless, for all the deviousness of banking malware, recent security news has been dominated by ransomware. Usually, ransomware hits hard and leaves you facing an immediate and unavoidable decision: “To pay or not to pay?”. As a result, you might be forgiven for assuming that web injects and banking malware were on the wane, which would be a huge mistake.

The Vawtrak gang have been getting strong lately. In fact, the hackers have evolved their malware, allowing their Crimeware-as-a-Service “customers” to target more victims at more banks in more countries.

Actually, Vawtrak is getting so strong that SophosLabs experts have written a follow-up report with a raft of new details:

“Since our previous analysis of the Vawtrak banking malware , there have been several important updates to the code and to the financial institutions and organizations being targeted. There have also been several widespread campaigns that have been utilized with great success to spread the new version of Vawtrak.”