The ransomware attacks keep increasing every day, and the only question regarding this issue is whether to pay or not to pay the ransome the victims are asked for. The answer of this question does not seem easy at all, while the internet devices infected with ransomware continue to mount.

According to The Global Applications and Network Security Report 2015 – 2016, over a third of the 311 organizations questioned worldwide had been struck by either ransom or SSL/TLS crypto algorithm attacks last year, the latter of which is used to steal credentials and other data from encrypted communications.

The motivation behind a quarter of the attacks in 2015 compared with only 16% the previous year, turned out to be the hackers’ attempts to gain a ransom in order to fund other cybercriminal activities.

But what exactly is ransomware and why is it such a problematic issue?

Ransomeware is a type of malware which first appeared in the shape of AIDS Trojan back in 1989, before most people even had computers. During that time, the ransomeware was distributed by floppy disk and either hid directories or encrypted/locked the names of files on infected machines’ C drives.

Nevertheless, the use of such programs for financial gain didn’t really take off seriously until 2005 when the industry started seeing the emergence of lots of fake tools for spyware removal or performance improvement, followed by bogus antivirus software a few years later.

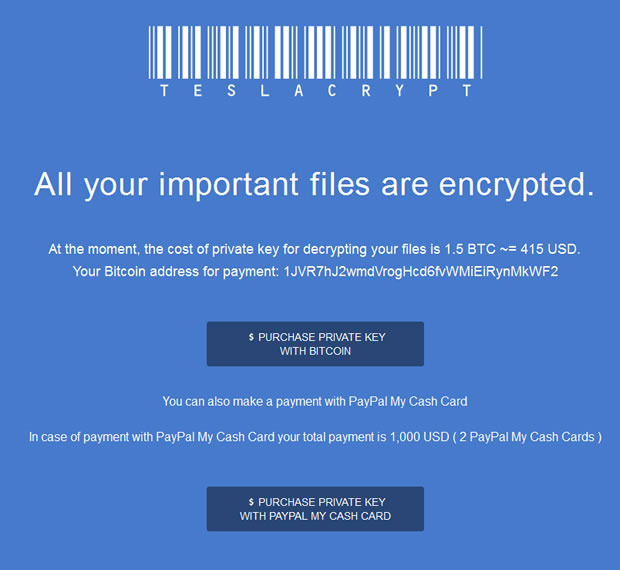

In 2011, a much more serious form of malware appeared in the shape of so-called “locker ransomware” such as CryptoLocker, which denies users access to their computer or device. This, in turn, was superseded by “crypto ransomware” such as CryptoWall, which encrypts files and data on devices’ hard disk, thereby preventing users from getting into them. Usually, most infections appear as a result of users opening infected email attachments or visiting a corrupted website.

However, much more concerning are the increasing attacks which hit 113% in 2015 compared with the year before. Though, the vast majority are simply blanket rather than specifically targeted attacks, while the use of spear phishing techniques is certainly rising up.

Most often, the ransomware targets financial services firms, internet service providers and organizations holding sensitive personal information such as healthcare bodies. Despite all the statistics made so far, the total size of the ransomware market remains unknown because many organizations do not report their misfortune.

An alert showed that between April 2014 and June 2015, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Centre had received nearly 1,000 notifications about CryptoWall. Victims reported losses from this variant alone of more than $18 million, but infections were estimated to be at least two or three times more than the number reported. The blog continues:

“Going by reported incidents only, it’s a $70 million per year criminal enterprise, but in reality it looks more like $200 million which is unbelievable. Some quick math shows $18,145 in costs per victim, caused by network mitigation, network countermeasures, loss of productivity, legal fees, IT services, and/or the purchase of credit monitoring services for employees or customers. As you can see, the total costs of a ransomware infection goes well above just the ransom fee itself, which is usually about $500 but can go up to $10,000.”

According to a group of cyber security product and service vendors who share threat intelligence, the damage done to both businesses and consumers by CryptoWall alone was in the region of $325 million worldwide. Regarding the average size of the ransoms, they appear to vary based on whom you talk to – and, interestingly, geographical region. For example, the security software provider Symantec reports that the usual fee is $300.

The preferred method of charging to open up locker ransomware-constrained devices is payment vouchers, while transactions for handing over the decryption keys for crypto ransomware are more likely to be conduced in bitcoins. The average ransom demanded in USA these days is around $700.

The ransom falls to around $500 for victims in Israel, Russia and Mexico though in order “to keep payments affordable” in line with average income. Nevertheless, in case users do not pay up before the ransom note expires, the amount required gets double.

Usually, the countries being most hit by ransomware are located in the developed world as people there tend to have the most money. Currently, on the top of the target list is USA, followed by Japan, the UK, Italy and Germany.

According to Joseph Bonavolonta, assistant special agent in charge of the cyber counterintelligence program at the FBI’s office, the encryption technology used in CryptoWall was so good that:

“To be honest, we often advise people just to pay the ransom.”

Bonavolonta was also cited as stating that the “overwhelming majority of institutions just pay”, not least because “you do get your access back”. But his comments caused a firestorm, with many a headline at the time questioning whether the FBI should really be encouraging organisations to pay cyber-criminals off, something they would never do if a ransom had been demanded for hostages.

Other security experts though, are completely adamant that affected organizations should never pay up – even though a study from 2014 suggested that as many as 40% do, including law enforcement agencies such as a local police department in Massachusetts.

David Emm, principal security researcher at internet security software provider Kaspersky Lab, commented:

“While it’s understandable that victims with no other alternative feel compelled to pay the ransom, the issue is very problematic. Paying the ransom validates the cybercriminals’ business model, leading to the development of more ransomware. It’s also important to remember that once paid, they may not provide the decryption key to recover the data. At the very least, paying up should be a decision of last resort, not a routine approach to the problem.”

The principal security response manager for Symantec’s security response team, Peter Coogan agrees:

“There’s no honor among thieves so there’s no guarantee that they’ll unlock your files even if you pay. And even if they do, they could just re-infect you and try to extort more money. But there’s no harm in giving it a go with negotiation. Each case is individual so there’s no way of knowing for sure if you’ll be successful, particularly as they hold all the cards. If you hit the sweet spot of $10,000, you can also possibly go to law enforcement, who it’s always worth reporting the situation to anyway.”

Regarding a case of the UK’s Lincolnshire County Council, it refused to pay an alleged ransom demand of £350 after a staff member opened an infected email attachment, but managed to contain the situation by taking down its network for four days – although not before the malware had spread to 300 machines.

According to Orlando Scott-Cowley, cyber-security strategist for email cloud services provider Mimecast:

“Lincolnshire suffered a classic attack. The ransomware was propagated thru network shares and so shutting its network down was the right thing to do – although taking systems offline is generally a last resort. It then restored them by rolling back its backup systems and so was able to deal with the situation quite effectively. So it was a happy ending – this time.”

No matter what the security experts say, the best way to deal with the ransomware is to prevent it from infecting your computer in the first place. The rest is to follow the usual security advice and make sure that:

- Your antivirus and web and email filtering software is kept up-to-date;

- Your operating systems, applications and browsers are patched promptly and regularly;

- Your systems undergo regular penetration testing to help you understand your risk profile and fix any potential problems;

- You have conducted proper scenario testing, have plans in place to deal with any attack, and communicate about it with employees and stakeholders, should disaster strike;

- Data backups are made regularly to offline storage in order to prevent the copying of encrypted files there too;

- End users are trained and reminded of good security behaviour, which includes not opening dodgy-looking email attachments and not downloading unknown applications.