ONI ransomware was found in Japan, earlier this year. According to security researchers, the threat is a sub-species of the GlobeImposter ransomware which, “When it infects it, it encrypts the file, assigns the extension .oni to the filename, and asks for payment to decrypt it.”

The experts from Cybereason claim that ONI is less ransomware, and more “a wiper to cover up an elaborate hacking operation.”

In their latest report, the researchers have tied the use of ONI to sophisticated attacks on Japanese industry. The incursions lasted between three and nine months, and only culminated in the use of ransomware. The threat was, in effect, used to hide the purpose and effect of the hack.

The Cybereason investigation revealed a new bootkit ransomware, called MBR-ONI, which modifies the MBR and encrypts disk partitions.

“We concluded that both ONI and MBR-ONI stem from the same threat actor since they were used in conjunction in the same targeted attacks and their ransom note contains the same email address,” the experts state.

The name ONI derives from the file extension of the encrypted files: ‘.oni’ which means ‘devil’ in Japanese. The term also appears in the contact email address used in the ransom notes: “Oninoy0ru” which can be translated as Japanese for ‘Night of the Devil’.

While analyzing the attack instances, Cybereason noticed a modus operandi. It started with successful spear-phishing attacks which led to the Ammyy Admin Rat introduction, followed by a period of reconnaissance and credential theft, and lateral movement “ultimately compromising critical assets, including the domain controller (DC), to gain full control over the network.”

The final stage of the attack is the use of log wipers and ONI distributed via a rogue group policy (GPO), in what Cybereason describes as a ‘scorched earth policy’. The GPO would copy a batch script from the DC server, wiping clean the Windows’ event logs to cover the attackers’ tracks and avoid log-based detection.

The batch file used the wevtutil command along with the “cl” flag, clearing events from more than 460 specified event logs. ONI would also be copied from the DC and executed, encrypting a large array of files.

The MBR-ONI ransomware is used more sparingly against just a handful of the endpoints. These were the critical assets such as the AD server and file servers. Despite the fact that both ONI and MBR-ONI could technically be decrypted (and can consequently be classified as ransomware rather than wipers), “We suspect,” the experts say, “that MBR-ONI was used as a wiper to conceal the operation’s true motive.”

The researchers also suspect that EternalBlue was used with other tools to spread through the networks. Despite the fact that the log wiping and the data corruption caused by the attacks makes this difficult to be confirmed, it was noted the EternalBlue patch had not been installed on the compromised machines, and the vulnerable SMBv1 was still enabled.

The ONI ransomware shares code with GlobeImposter, and shows Russian language traces. “While this type of evidence could have been left there on purpose by the attackers as decoy,” the experts state, “it can also suggest that the attacks were carried out by Russian speakers or, at the very least, that the ransomware was written by Russian speakers.”

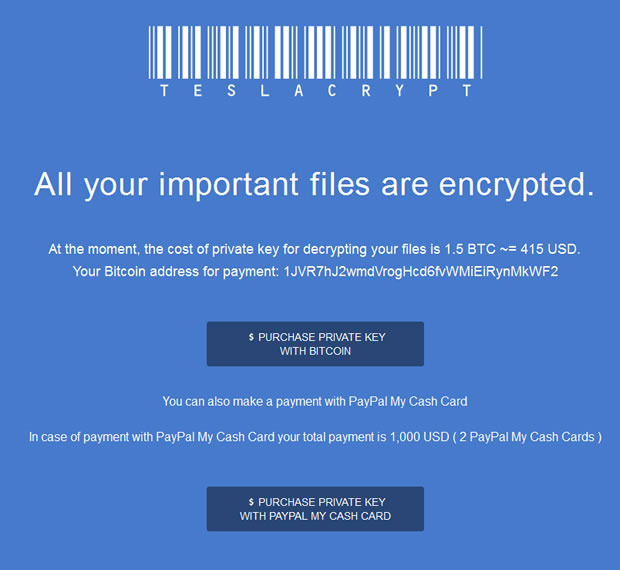

The MBR-ONI ransomware uses the same ransom message and ID for all infected machines. A modified version of the open-source DiskCryptor tool was used for the encryption. Although this could be decrypted if the attackers supply the right key, “we suspect that the attackers never intended to provide recovery for the encrypted machines. Instead, the program was meant to be used as a wiper to cover the attackers’ footprints and conceal the attack’s motive.”

According to the experts, it is unlikely that financial gain is the only motive for the ONI attacks in Japan. The researchers also note that there are increasing reports of ransomware being used as a wiper by both cybercriminals and nation states in other parts of the world.